Let’s Get Wellington Moving… in the 1920s

A century ago, Wellington City Council was dealing with similar issues to those facing planners today: how to manage shifts to new modes of transport and how to keep traffic moving safely and freely.

The 1920s saw much of Wellington transformed with huge investments in new infrastructure and a shift to new modes of transport. Much of this change was driven by the rise in the popularity of motor vehicles after World War I. Before the war, cars were primarily toys for the very wealthy, but technological advancements and increasing standards of living saw them become aspirational products for the middle class in the post-war period. For much of this early period in our automotive history, most cars were imported as a basic chassis with motors and running gear already installed. It would then be left to local coachbuilders who had adapted their skills in making buggies and carts, to turn this basic building block into a ‘car’. Two examples of the same make and model of car could end up looking very different to each other depending on which coachbuilder had been contracted to complete each vehicle.

Under the Motor Regulation Act 1908, the Wellington City Council took control of all motor vehicle licensing, the issuing of number plates and annual vehicle registration. Concerns were soon raised about the safety of Wellington’s early car drivers. In 1916 fewer than half the drivers of the roughly 1000 vehicles registered in Wellington actually held ‘certificates of competency’ (i.e. a driver’s licence) and accidents were common. On-street parking within the inner-city was actually banned until 1917 when increasing demands from vehicle owners finally saw the council relent and motor vehicles were allowed to be parked for limited periods for the first time (much to the chagrin of the owners and drivers of horse-drawn vehicles). With increasing car importations (especially of complete cars) and large disparities in the manner that different councils were administering vehicle licensing, the passing of the Motor Vehicles Act in 1925 saw the government take full control of the issuing of number plates, recording ownership changes, annual registration and drivers’ licensing; all of which was administered by the Post Office. However, local councils were still able to dictate how motor vehicles could operate and drivers had to be aware of different bylaws which were in place in different parts of greater Wellington.

After sales of complete cars became more common in the1920s, coachbuilders sought to maintain their trade by offering vehicle ‘rejuvenation’ services.

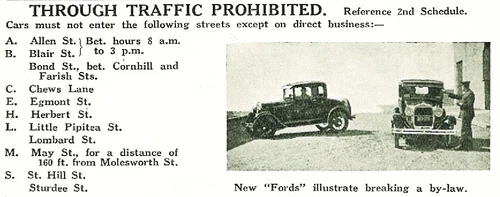

The concept of closing streets to private motor vehicles is not new. Many other roads had parking and turning prohibitions in place to improve traffic flows and a team of Council Traffic Inspectors were employed to enforce rules and impose fines.

In 1929, the City Council published The Complete Wellington Guide, in part to promote the capital to tourists but also to educate locals on the somewhat complicated rules around owning and operating a motor vehicle. For example, in Wellington the speed limit was set at 25 mph (40 kph) but this dropped to 15 mph (24 kph) outside schools, hospitals, close to any intersection or when passing a stopped tram travelling in the opposite direction. To further complicate matters, Lower Hutt had a main street speed limit of 20 mph (but 10 mph crossing the Hutt River and Melling bridges) while most of Petone’s streets had a speed limit of only 15 mph. There were several rules regarding cars driving around trams, including no passing of any tram that had stopped in the road and no passing on the ‘off side’ (i.e. to the right) of any tram at any time be it moving or stationary (similar rules remain in Melbourne to this day).

A bylaw introduced by the council in 1928 saw a multitude of different traffic rules for Wellington formalised including setting the traffic flow direction of Kent and Cambridge Terrace and declaring several streets to be one-way only (e.g. Dixon Street from the Taranaki Street intersection). Many of these rules remain current in 2022. A detailed map was printed instructing drivers where they could park in the inner-city and for how long. Parking meters were not introduced until 1954 so it was left to staff of the WCC Traffic Department to enforce parking rules and time limits. Street maps of the entire city were included in the Complete Guide, as well as the Petone, Lower Hutt and Eastbourne boroughs. These give an interesting insight into how our city has grown since the booklet was published. Tourist information included details about Wellington bus tours, rail excursions and day-trip suggestions for those lucky enough to own a car. Special emphasis was placed on the hunting and fishing opportunities available in the wider region, with a provincial map showing what types of game could be found in different areas. Hunting and trout fishing were widely promoted and often used to advertise the region to potential or newly arrived British migrants, many of whom were staggered to discover that pursuits which were largely restricted to the aristocracy and upper-classes in the UK were so available to the ‘common man’ in Wellington.

Softer road surfaces which were suitable for horses hooves and steel-rimmed cart wheels were problematic for the pneumatic tires of cars. Here council workers seal Victoria Street with ‘Macadam’(i.e. asphalt) in March 1926. Bitumen was sourced as a by-product of New Zealand’s first oil refinery which had opened in New Plymouth in 1913. Ref: 50010-121

Courtenay Place photographed only about six years after the first photo, illustrating just how quickly motor vehicles replaced horse-drawn transport in the 1920s. ATL Ref 1/2-048940-G