New online resource: the Wellington Provincial Council Gazette, 1854-1876

Digitised for the first time is the collection of the weekly gazette of the Wellington Provincial Council, which offers a fascinating insight into the city and region’s early colonial history.

From 1853 through to 1876, New Zealand operated a quasi-federal system of provincial government where each province had its own mini-parliament to manage local affairs. Initially six provinces were established. The Wellington Province extended above Whanganui in the west and to Wairoa in east (though Hawke’s Bay would later split off to form its own province in 1858) but for much of the council’s existence, its focus was often concentrated in and around Port Nicholson.

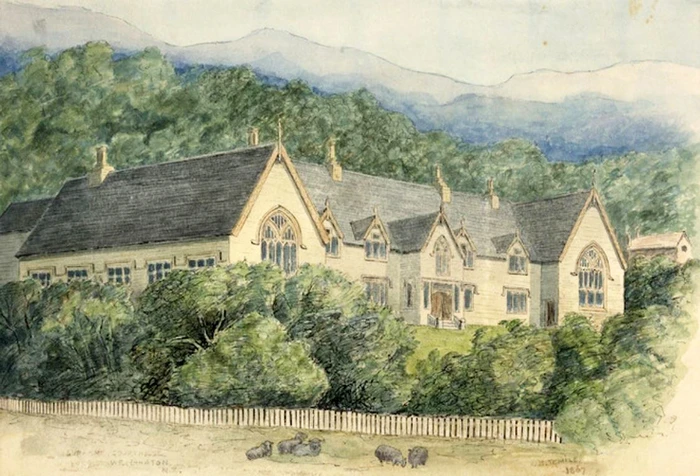

Sheep graze outside the Wellington Provincial Council chambers once located on the site of the current parliamentary library. ATL Ref: B-079-008

Operating from a building constructed on what was later to become the parliamentary grounds, members were chosen in regular elections which were open to men aged 21 years or older who owned freehold property worth at least £50. Voters also got to elect a ‘superintendent’ who was not a Council member but acted as a quasi-chief executive for the province. For most of its 23-year existence, the dominant superintendent was Isaac Featherston after whom both the central Wellington street and the south Wairarapa township were named. From September 1854 the Wellington Provincial Council published a near-weekly ‘gazette’, an official magazine that reported on a huge variety of different administrative concerns. For its first decade it was printed on blue paper stock by The New Zealand Spectator, a weekly newspaper based in Manners Street which had been contracted by the Council to produce the magazine. The colour chosen directly referenced that used by the British House of Commons which had all its sessional publications (known as the ‘Blue Books’) printed in this manner.

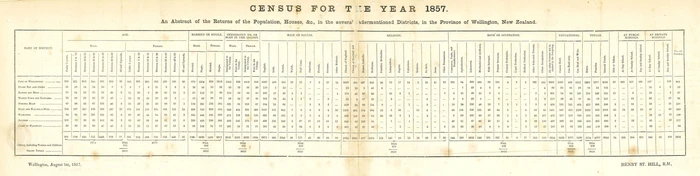

The 1857 Wellington census results as published in the gazette.

The Gazette was used to record official proclamations and as firmly stated below its masthead “All public notifications which appear in this gazette…are to be considered as Official Communications made to those Persons to whom they may relate, and are to be obeyed accordingly”. However, the size and scope of the information printed was huge and this offers both an insight into Wellington’s early economy & society as well as a valuable source of genealogical information for family historians. Details include council election results, electors lists, census results, numbers of migrants and the amount & type of goods being landed at the port. Returns from local sheep farmers would be regularly reported including stock numbers, the size of farms and the overall health of the animals (infectious animal diseases being of great concern to authorities). Local bankruptcies and legal disputes that ended up in court are also covered.

Annual reports provided by local institutions such as prisons, hospitals and schools were a regular feature as were reports by ‘commissions’ investigating major events. One such report appeared at the end of 1855 looking at the impact of the massive 8.2 magnitude earthquake that struck on the evening of 23rd January which devastated the region. The commissioners found themselves having to grapple with the inherent problem that buildings which were most resistant to fire (a constant threat in colonial settlements) were also the most prone to collapse in major earthquakes (and vice-versa). Recommendations were made suggesting that unreinforced brick buildings constructed using traditional British brick-laying methods were completely unsuitable for Wellington and the system should immediately be abandoned. Shatter-tests were carried out on a wide selection of different native timbers to see which was best suited for use as framing and structural reinforcement.

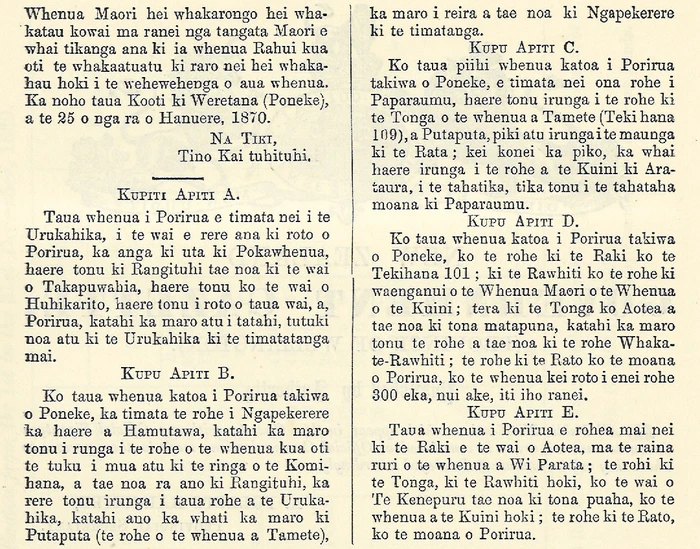

Te Reo Māori was regularly used in the gazette, often in relation to the ‘Native’ Land Court determining land claims, ownership by individual Māori or when iwi wished to subdivide large holdings into smaller plots. One example is the following text published on 17 January 1870 advising of a meeting of the Land Court to be held on the 25th of that month to determine the owners of five large sections of land located around Porirua Harbour and inviting all interested parties to attend.

With improvements in infrastructure and communication, the need for provincial councils began to decline. Some councils had also taken on considerable debt which often left them in a precarious financial position (this led to Southland amalgamating with the Otago province 1870). In 1865, central Government shifted from Auckland to Wellington with the first sitting of the new Parliament taking place in the Wellington Provincial Council’s chambers on 26th July. Around the same time prototype local authorities began to form with the establishment of various ‘Town’ and ‘Highway’ boards who were given the power to charge residents rates to fund the construction of roads and to control ‘nuisances’ such as wandering stock and the illegal dumping of rubbish.

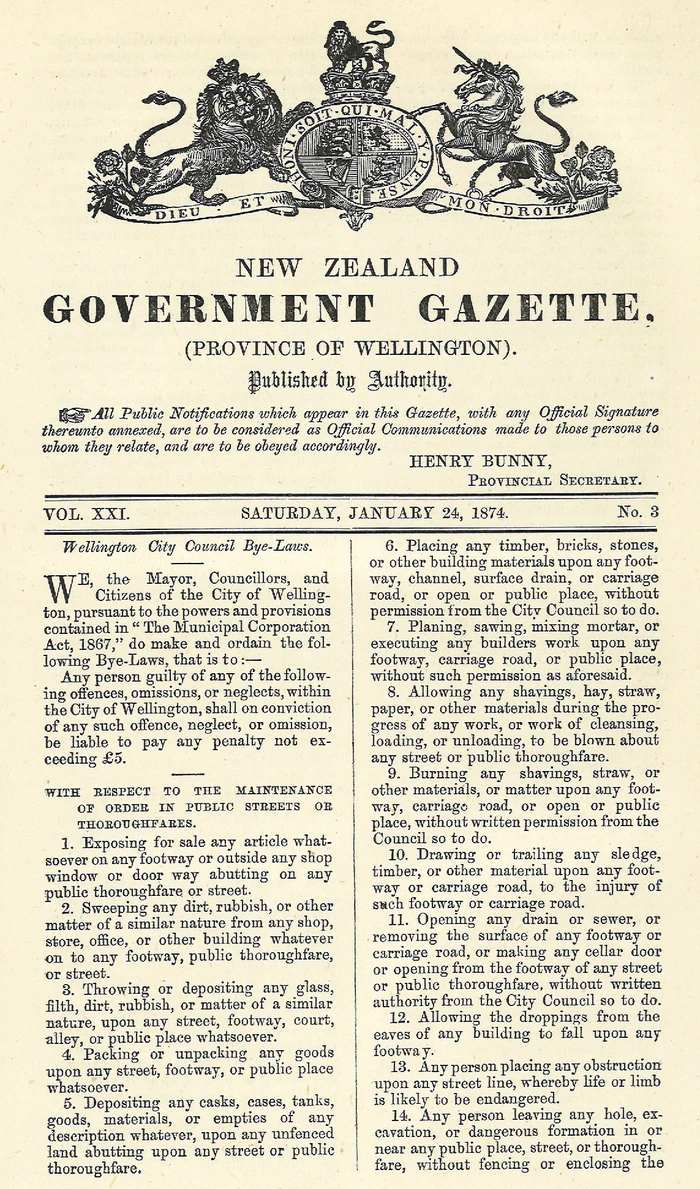

WCC bylaws printed in the gazette in January 1874

In the capital, these eventually gave way to the formal establishment of the Wellington City Council in 1870 which began to take over many of the roles formerly conducted by the Provincial Council though they were still required to ratify local bylaws. The 1870s also saw divisions in parliament between “Centralists” who favoured a strong central government and “Provincialists” who preferred strong regional governments which some envisaged could develop along similar lines to the federal systems used in Australia and the United States. Friction between provinces saw absurdities arise such as different regions selecting different railway gauges or ‘pork barrel politics’ where local politicians would lobby central government to fund projects specifically to benefit their own region (and thus increase their popularity with voters). From 1873, the government of Sir Julius Vogel undertook massive borrowing to invest into transport infrastructure and the adoption of a standard rail gauge. His vision of New Zealand being a unified “Britain of the South Seas” sapped the power of the Provincialists and after a vote passing the Abolition of Provinces Act 1875, the period of provincial government formally came to an end on 1 January 1877. Remarkably, a small remnant of this period in New Zealand’s history survives in common use to this day; the areas which are covered in each region’s Anniversary Day holiday are still determined by the old provincial boundaries as they existed in 1876.