The 1951 Waterfront Dispute: 151 days that shook New Zealand

2021 marked the 70th anniversary of the longest labour dispute in Aotearoa’s history. A selection of pamphlets and newsletters from the Wellington Waterside Workers’ Union is now on Recollect.

An illegal flyer printed to be handed out to the public to explain the position of the Wellington Waterside Workers’ Union. Emergency regulations meant any coverage of their views by news media was banned by the government.

Though it is now passing from living memory, the 1951 Waterfront Dispute remains one of the most contentious industrial conflicts from our past. Lasting 151 days, it was the longest serious industrial action ever taken in New Zealand and involved more people than any other strike in our history with over 22,000 members of the Waterside Workers’ Union and other sympathetic labour groups involved. It was a deeply divisive and polarising event with different sides accusing each other of being ‘communists’ or ‘fascists’ respectively with many of the attacks becoming increasingly personal and vindictive. Even the name and nature of the event was in dispute with the Government, port authorities and shipping companies calling it a ‘strike’ and the waterside workers calling it a ‘lock-out’. This distinction remained a contentious issue among some historians and political scientists for decades after the event.

The dispute had its origins in the restrictions the government placed on the economy which were deemed necessary during the Second World War. However, in the immediate post-war years the local economy started to boom with high immigration from the UK and excellent export prices for NZ agricultural products by the late 1940s. This increased further after the start of the Korean War in 1950 led to a huge spike in international wool prices. Many working-class labourers felt that they were missing out on the ‘spoils of victory’ as inflation rose and the cost of living spiralled upward. The then-Labour Government introduced compulsory military conscription in 1949 in response to the Cold War and to attract the votes of war veterans but this action antagonised many in the union movement. Though conscription was supported by the more conservative elements in society, the Labour Party lost the 1949 election to National and Sid Holland became Prime Minister. He promised to ease war-time restrictions which had remained in place such as butter and petrol rationing and to take on those unions which many felt were becoming more militant and were possibly receiving support from the Soviet Union. In April 1950 the industrial labour movement split when the Waterside Workers and other militant unions left their ‘umbrella’ organisation the Federation of Labour (F.O.L.) and together formed a breakaway group, the Trade Union Congress (T.U.C.).

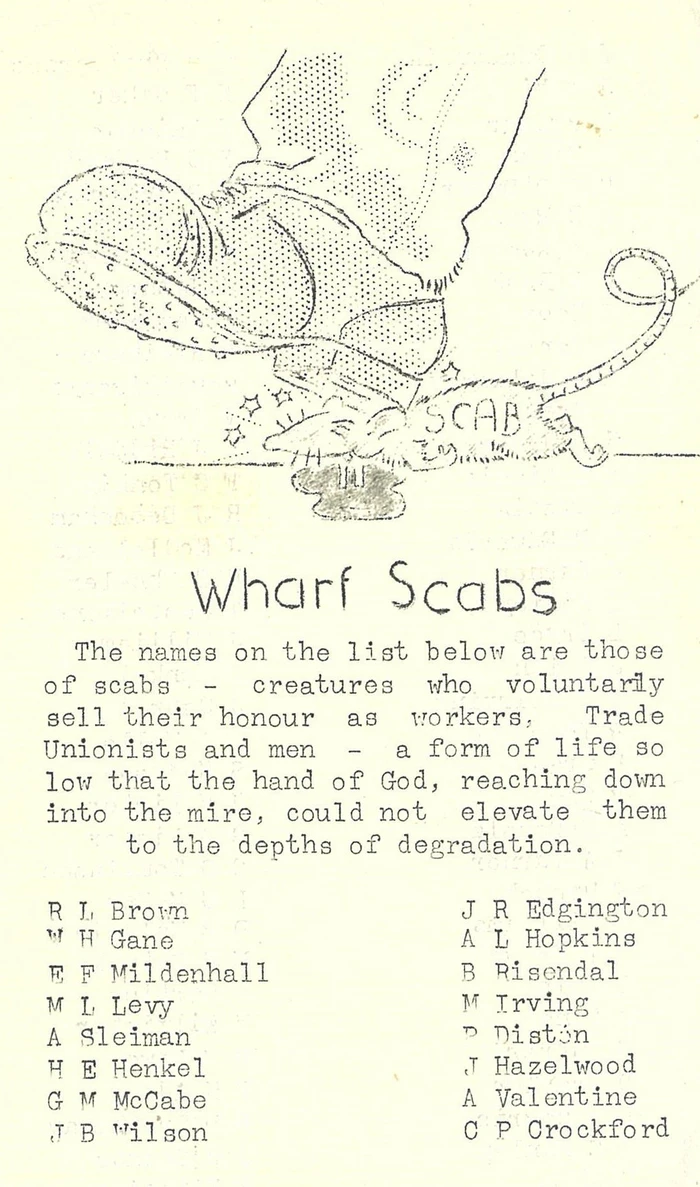

A double-sided flyer listing the names of strike-breakers who returned to work against the Waterside Workers’ Union’s wishes

In early 1951 the Arbitration Court awarded a 15% wage increase to workers covered by the industrial arbitration system. However, this did not apply to ‘wharfies’ as their pay rates were controlled by a separate industry ‘commission’ which was heavily influenced by the mostly British-owned shipping companies who offered only 9%. The Wellington Waterside Workers’ Union protested by refusing to work overtime from 13th February. The shipping companies in turn refused to employ them unless they agreed to work the extra hours requested. When no agreement could be met, union members were ‘locked out’ from Wellington’s wharves (a time when the inner-harbour port area was surrounded with high fences and tight security) and shipping across the country soon ground to a halt with Wellington and Auckland becoming the main centres of the dispute. This was an era where shipping was hugely important to both the internal and export economy and the event had a dramatic impact on people’s lives as shortages of goods began to occur. Disrupted coal supplies threatened electricity production and the ability for people to heat homes, schools and businesses during the winter. Sid Holland declared a national State of Emergency and made soldiers load and unload ships in Wellington and Auckland but their lack of experience in handling freight or operating cranes meant that the flow of goods ‘bottlenecked’ on wharves and this soon spread throughout the rest of the supply chain. Regulations imposed strict censorship, gave police sweeping powers of search and arrest with the barest suspicion and made it illegal for anyone to help strikers or their families; even giving food to their children was a prosecutable offence.

A pamphlet vilifying Arthur Kingsley Bell, president of the break-away Wellington Maritime Cargo Workers’ Union

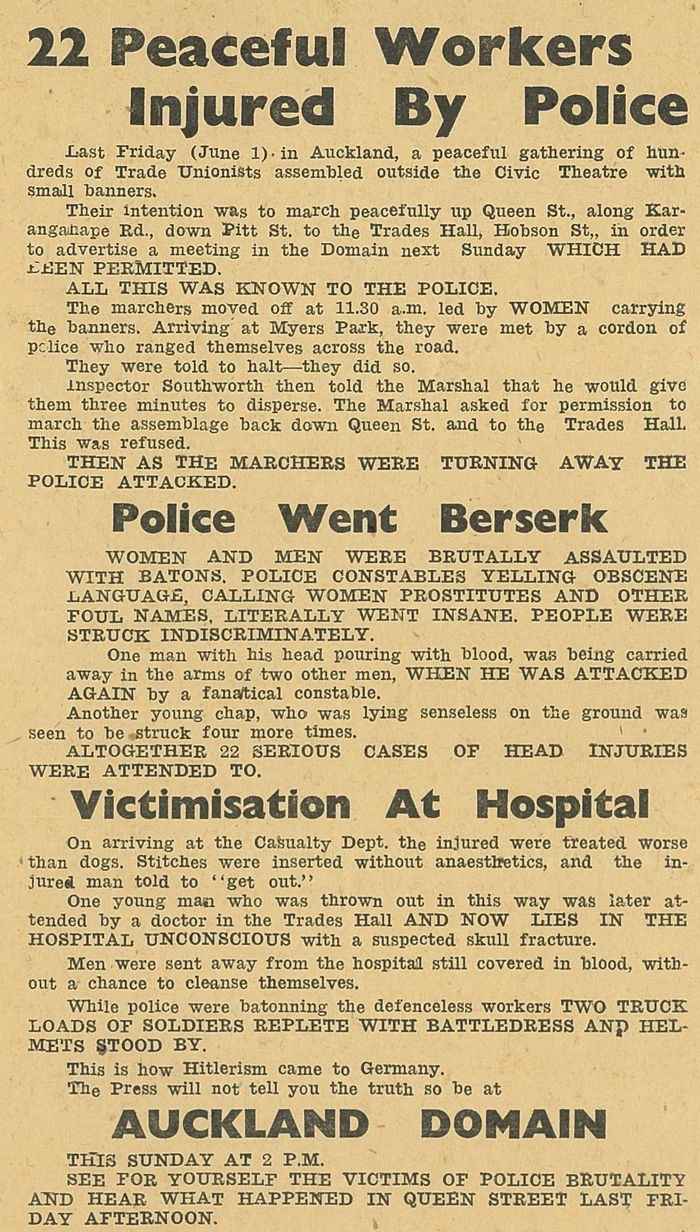

Despite the number of people involved, the total number of strikers was actually less than 10% of the total union movement and the more militant unions’ hopes that the dispute would turn into a general strike came to nothing. Though the Labour Party opposed the government’s emergency regulations, they didn’t want to alienate moderate voters and so refused to support the striking workers. Sensing victory, the National Government increased their hard-line stance and urged the police to take strikers head-on. Though there were multiple skirmishes in Wellington, the most violent incident happened in Auckland on 1st July 1951 when police baton-charged a protest march on Queen Street. This pamphlet (left) advertises a gathering the following week in the Auckland Domain where organisers hoped to explain what happened at the earlier event from their point of view as censorship had prevented any media coverage. However, as increasing numbers of workers shifted over to the new unions desperate for work and to feed their families, after a five month struggle, on 15 July 1951 the striking unions finally conceded defeat.

An illegal flyer issued following a police attack on an Auckland protest march.

Shortly after the dispute ended, Sid Holland called New Zealand’s first snap election only two years into his three-year term, hoping to give his National Government a mandate to react strongly against any further industrial action. By concentrating on militant unions, he also deflected attention away from rising inflation which could have become an election issue had parliament run to its full three-year term. The campaign was said to be one of the ‘dirtiest’ in New Zealand’s electoral history with suggestions being made that the new Labour leader Walter Nash might be a ‘fellow traveller’ (i.e. a communist supporter) on account of his 1936 visit to Moscow (despite the fact that this was an official trade mission in his former capacity as Minister of Finance when he also visited London and Berlin). The Labour Party tried to walk a moderate line between striking workers, the establishment and the general public but ended up displeasing all sides and National was returned in a land-slide victory with an increased majority.

You can view our complete collection of newsletters, newspapers and leaflets relating to the 1951 dispute here.